Once celebrated in home gardens, farmer’s markets, and early American kitchens, these 17 vegetables were staples of everyday life—until they weren’t. Quietly pushed aside by modern agriculture, shifting tastes, and commercial convenience, they’ve nearly vanished from our plates and memories. From heirloom beans with stunning speckles to ancient grains cultivated by Native peoples, each tells a story of regional flavor, cultural heritage, and lost culinary potential. Some were replaced by more uniform hybrids, others simply faded into obscurity. Ready for a bite of the past? Here are the long-lost vegetables that once defined American dining—and why they disappeared.

1. Boston Pickling Cucumber

Once the darling of New England kitchens, these small, crisp cucumbers created the perfect crunch in homemade pickles. Their thin skins and firm flesh absorbed brine beautifully, creating that signature tangy snap.

Families would dedicate summer days to preserving these little gems for winter enjoyment. Grandmothers passed down prized pickling recipes featuring these special cucumbers.

Modern hybrid varieties, bred for uniform appearance and disease resistance, gradually replaced these heritage cucumbers. Commercial producers favored varieties that could withstand mechanical harvesting and long-distance shipping, qualities the delicate Boston cucumber couldn’t match.

2. Tennessee Sweet Potato Pumpkin

Bakers throughout the South once treasured this bell-shaped pumpkin for its exceptional pie-making qualities. The sweet, dense flesh offered notes of chestnut and maple that modern varieties simply can’t match.

Rural families cultivated these pumpkins specifically for holiday desserts. The distinctive tan exterior hid vibrant orange flesh perfect for custards and preserves.

As supermarkets demanded pumpkins with consistent size and appearance, the Tennessee Sweet Potato Pumpkin faded away. Commercial farms abandoned it for varieties that produced predictable yields and survived shipping better, sacrificing flavor for practicality.

3. Spotted Bean Varieties

Gardens across America once showcased a rainbow of spotted beans – Tiger’s Eye with gold and maroon swirls, Jacob’s Cattle dotted like Holstein cows, and Rattlesnake beans with purple streaks. Each variety brought unique flavors and cooking properties to family meals.

Rural communities took pride in preserving their special bean varieties. Seed-saving became a tradition, with neighbors exchanging their best performers each spring.

The rise of canned goods and focus on mass-produced varieties like navy and kidney beans pushed these colorful legumes aside. Modern consumers, unfamiliar with these heirloom varieties, gradually lost the knowledge of how to prepare them, further accelerating their decline.

4. Cardoon

Looking like prehistoric celery with silvery leaves, cardoon was once a wintertime treat in Italian-American gardens. The blanched stalks offered a delicate artichoke flavor when properly prepared.

Growing cardoon required patience and skill. Gardeners would wrap the plants in paper to blanch them, reducing bitterness and creating tender stalks.

Modern Americans, pressed for time and unfamiliar with traditional preparation methods, gradually abandoned this labor-intensive vegetable. Few home cooks today recognize cardoon, let alone know how to prepare it properly by removing the stringy fibers and bitter skin before braising or frying the delicate hearts.

5. Wild Cucumber

Native American tribes introduced early colonists to this unusual squash with its distinctive peppery flavor. Unlike modern cucumbers, wild cucumbers were eaten cooked rather than raw, often paired with game meats.

Colonial cookbooks featured recipes highlighting their unique taste. The plant’s sprawling vines produced abundantly in summer gardens throughout the Eastern seaboard.

Changing American palates and the standardization of vegetable varieties gradually pushed this distinctive squash into obscurity. Modern consumers, accustomed to mild-flavored vegetables, found its assertive taste too unusual, and farmers abandoned it for more marketable crops.

6. Montreal Melon

Railroad passengers once eagerly anticipated stops in Montreal where vendors sold slices of this legendary melon. Weighing up to 20 pounds, these green-fleshed muskmelons captivated with their intoxicating nutmeg fragrance and exceptional sweetness.

Farmers around Montreal dedicated prime fields to these valuable fruits. Hotels and fine restaurants featured them prominently on menus, charging premium prices for perfect specimens.

Urban development swallowed the fertile island soil where these melons thrived. By World War II, the Montreal Melon had virtually disappeared, with only a few seed savers maintaining this legendary fruit that once sold for the equivalent of $60 in today’s currency.

7. Pitseed Goosefoot

Long before European contact, Native Americans across eastern North America cultivated this productive grain. Similar to quinoa (its close relative), Chenopodium berlandieri produced nutritious black seeds that formed a dietary staple.

Archaeological evidence shows sophisticated farming systems dedicated to this crop. Indigenous communities developed specialized tools for harvesting and processing these tiny, protein-rich seeds.

European colonization disrupted traditional agriculture patterns, and introduced crops gradually replaced native foods. Modern agricultural research has revealed that domesticated goosefoot was nearly as nutritionally valuable as modern grains, making its loss particularly significant from both cultural and nutritional perspectives.

8. Maygrass

Before corn dominated American fields, Eastern Woodland tribes carefully cultivated maygrass for its nutritious seeds. This humble-looking plant produced abundant harvests of small grains perfect for porridge and bread.

Archaeological sites reveal maygrass seeds were stored in significant quantities. Indigenous farmers developed sophisticated techniques to encourage its growth in managed landscapes.

The introduction of maize agriculture gradually displaced this ancient grain. Modern Americans rarely recognize that native communities maintained complex agricultural systems long before European contact, with maygrass playing a crucial role in food security. Today, this once-important crop exists primarily in seed banks and archaeological collections.

9. Little Barley

Native communities throughout the Mississippi Valley once harvested fields of this productive grain. Little barley matured earlier than other crops, providing crucial spring nutrition when winter stores ran low.

Indigenous farmers developed sophisticated techniques for growing this grain. They created tools specifically designed for harvesting the small but abundant seeds.

The European introduction of wheat and barley, along with disruption of traditional farming practices, led to little barley’s agricultural extinction. Modern archaeologists have found carbonized little barley seeds at numerous pre-Columbian sites, revealing its importance in ancient diets and challenging the misconception that Native Americans were primarily hunter-gatherers rather than skilled agriculturalists.

10. Erect Knotweed

Native Americans transformed this wild plant into a productive crop through careful selection. The small black seeds, rich in protein and oil, provided essential nutrition through harsh winters.

Archaeological evidence shows knotweed was cultivated for over 2,000 years. Indigenous farmers selected for larger seeds and more productive plants over countless generations.

European colonization disrupted traditional agricultural systems, and knotweed cultivation was abandoned. Today, wild knotweed is considered an annoying weed by most Americans, who remain unaware of its incredible food potential and historical importance. Recent interest in native foods has sparked small efforts to re-domesticate this forgotten crop.

11. Sumpweed

Ancient farmers throughout the Eastern Woodlands cultivated this remarkable oilseed crop for thousands of years. Sumpweed seeds contain more protein and oil than soybeans, making them nutritional powerhouses.

Indigenous agriculturalists selectively bred wild sumpweed into a productive crop. The seeds increased dramatically in size under human selection, from tiny wild versions to plump cultivated forms.

Despite its impressive nutritional profile, sumpweed has major drawbacks – it causes allergic reactions in many people and smells distinctly unpleasant. As maize agriculture spread northward from Mexico, this native oilseed lost its agricultural importance. Today, it survives only as a wild plant, with its domesticated forms functionally extinct.

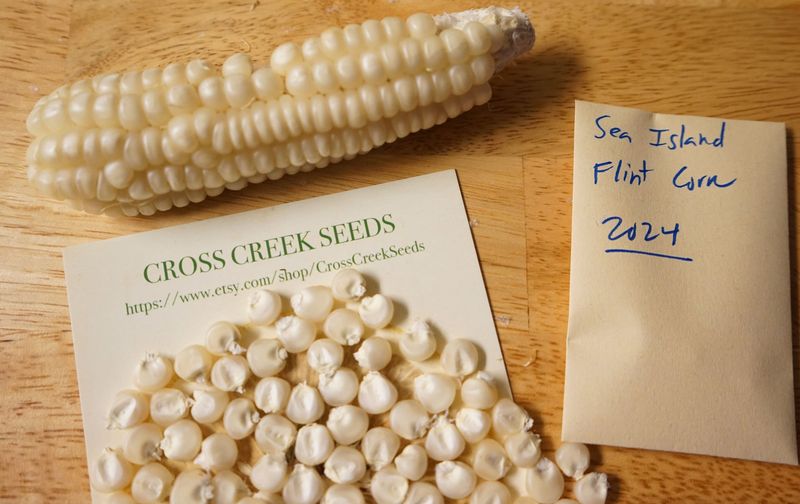

12. Sea Island White Flint Corn

Gullah communities along the Carolina and Georgia coast once treasured this distinctive corn variety. Its pearly white kernels produced exceptionally fine grits and hominy with delicate flavor unlike modern hybrid corn.

Enslaved Africans and their descendants developed this variety through careful selection. The corn adapted perfectly to coastal growing conditions, thriving in sandy soil and high humidity.

Industrial agriculture and changing food habits pushed this heritage corn toward extinction. Hurricane damage to coastal communities further threatened seed stocks. Today, a handful of dedicated farmers and the Slow Food Ark of Taste program work to preserve this living piece of African American agricultural heritage.

13. Amber Sorghum

Rural families once anticipated fall sorghum-making days with excitement. The tall amber canes were stripped, crushed, and the juice boiled down into rich, molasses-like syrup that sweetened winter meals.

Community sorghum-making became social events in many regions. Families would gather to help process the harvest, sharing stories while the fragrant syrup bubbled in large evaporator pans.

Refined sugar became more affordable and convenient after World War II, reducing demand for home-produced sweeteners. Modern farmers switched to varieties optimized for grain production rather than syrup. The specific amber varieties once prized for their superior flavor gradually disappeared, though sorghum syrup production continues on a small scale in parts of Appalachia and the South.

14. Tomato Fig

Early American gardeners prized this unusual pear-shaped yellow tomato for its unique sweetness. Unlike modern tomatoes, these were often preserved whole in sugar syrup as “tomato figs” – a confection that graced special occasion tables.

Victorian cookbooks featured numerous recipes for this forgotten delicacy. The preserved tomatoes resembled actual figs in appearance and somewhat in texture, hence the curious name.

Changing preservation methods and declining home canning led to this variety’s disappearance. Few modern gardeners recognize these specialty tomatoes or understand their historical culinary purpose. The unique preparation technique – preserving tomatoes as sweet treats rather than savory items – represents a lost chapter in American food culture.

15. American Persimmon

Native persimmon trees once provided sweet autumn treats across eastern forests. Unlike their Asian cousins found in supermarkets today, American persimmons are small, seedy fruits with incomparable honey-spice flavor that develops only after frost.

Rural families knew exactly when to harvest these wild fruits. The timing was crucial – picked too early, the astringent fruit would turn your mouth inside out; perfectly ripe, they offered nature’s pudding.

Commercial development favored larger, less finicky Asian varieties that ship well. Traditional recipes for persimmon pudding, beer, and bread faded from family tables. Though wild trees still produce abundantly, few Americans today recognize these native fruits or understand how to properly enjoy their unique sweetness.

16. Louisiana Purple Sugar Cane

Early Louisiana plantations cultivated distinctive purple-stemmed sugarcane varieties brought from the Caribbean. These heirloom canes produced complex-flavored sugar with subtle molasses notes that modern refined products can’t match.

Skilled sugar makers developed techniques specific to these varieties. The raw sugar retained purple-tinged crystals and depth of flavor lost in modern processing.

Agricultural industrialization favored higher-yielding varieties with improved disease resistance. Traditional sugar-making knowledge disappeared along with these historic canes. Today, only a few preservation-minded farmers maintain these heritage varieties, which represent living artifacts of American culinary history and the complex legacy of plantation agriculture.

17. Mission Fig

Spanish missionaries introduced these sweet figs to California, where they flourished around mission gardens. The distinctive purple fruits with ruby flesh became signature treats in early California cuisine.

Orchards of Mission figs once dotted the California landscape. Families dried the abundant summer harvest on rooftops to enjoy throughout winter months.

Commercial fig production shifted toward varieties better suited for mechanical harvesting and shipping. The delicate Mission figs bruised easily and required careful handling. While not completely extinct, true heritage strains of Mission figs have become increasingly rare, replaced by more commercially viable varieties that lack their distinctive flavor profile and historical significance.

Leave a comment