Tucked away on quiet Amish farms are vegetable varieties most modern grocery shoppers have never seen—let alone tasted. Gnarled, oddly shaped, and often overlooked by mainstream agriculture, these heirloom gems are anything but ordinary. The Amish, known for their self-sufficiency and time-honored growing practices, have preserved these “ugly” yet incredibly flavorful vegetables for generations. From knobby roots to forgotten greens, each one tells a story of resilience, tradition, and rich culinary potential. If you’ve only been eating supermarket standards, you’re missing out. Here are 16 rare and delicious vegetables the Amish still grow—and you’ll wish you discovered them sooner.

1. Salsify: The Oyster-Flavored Root

Long, skinny, and covered in dirt-trapping fuzz, salsify won’t win beauty contests but certainly earns its place in Amish gardens. The white flesh develops a curious oyster-like flavor when cooked, explaining its old nickname “oyster plant.”

Amish farmers harvest these roots after the first frost when their starches convert to sugar. Most modern Americans have never tasted this Victorian-era favorite, but Amish cooks transform it into velvety cream soups or simply mash it with butter and cream.

The plant produces beautiful purple flowers if left unharvested, serving dual purposes in traditional Amish gardens where beauty and function intertwine.

2. Ground Cherries: Tiny Fruits in Paper Lanterns

Resembling tiny tomatillos in miniature paper husks, ground cherries are nature’s candy with a surprising tropical flavor. Amish children often collect these fallen treasures from beneath plants, where they ripen to golden perfection inside their papery wrappers.

The sweet-tart taste combines hints of pineapple, vanilla, and tomato into something entirely unique. Amish bakers fold them into pies, preserves, and jams that capture summer’s essence for winter enjoyment.

Hardy and self-seeding, these plants return year after year in Amish gardens, requiring minimal care while producing abundantly—a perfect match for their practical farming philosophy.

3. Kohlrabi: The Alien Vegetable

With its UFO-shaped bulb and tentacle-like stems, kohlrabi looks like something from another planet rather than an Amish garden. Young Amish farmers often introduce visitors to this odd-looking brassica by offering crisp, sweet slices straight from the garden.

The pale green or purple bulb grows above ground, developing a flavor that somehow combines broccoli stem, cabbage heart, and apple. Many Amish families enjoy it raw in slaws or salads, though older, larger bulbs are typically peeled and roasted until tender.

Kohlrabi thrives in cool weather, making it perfect for spring and fall harvests in Amish communities across Pennsylvania and Ohio.

4. Rutabaga: The Forgotten Winter Root

Lumpy, wax-coated, and often confused with turnips, rutabagas aren’t winning popularity contests in modern markets. Yet Amish farmers treasure these homely roots for their remarkable storage properties and frost-sweetened flavor.

Harvest typically happens after the first hard frosts have converted starches to sugars, intensifying the root’s earthy sweetness. The yellow flesh becomes rich and buttery when roasted or mashed, earning it a place at many Amish winter tables.

Rutabagas store for months in cool cellars, providing essential nutrition through long winters when fresh produce was historically scarce—a practical consideration that keeps this vegetable in Amish crop rotations.

5. Celeriac: Beauty’s Knobbly Cousin

Gnarled, hairy, and resembling a brain more than a vegetable, celeriac might be the ugliest produce in the Amish garden. This bulbous root hides beneath ordinary-looking celery foliage, developing its distinctive celery flavor underground.

Amish cooks peel away the rough exterior to reveal crisp white flesh perfect for winter soups and gratins. The flavor mellows and sweetens with cooking, offering celery’s aromatic qualities without stringiness.

Particularly valued in Pennsylvania Dutch cooking, celeriac appears in traditional dishes that German-speaking ancestors brought to America generations ago, connecting modern Amish tables to their European heritage.

6. Parsnips: Winter’s Sweet Secret

Resembling albino carrots with their pale cream color, parsnips rarely appear in modern shopping carts despite their fascinating transformation after frost. Amish farmers leave these roots in the ground until after several hard freezes turn their starches into complex sugars.

The resulting harvest brings intensely sweet, nutty flavors that nineteenth-century cooks once used as natural sweeteners. Modern Amish families roast them until caramelized or add them to hearty stews where they contribute subtle sweetness.

Parsnips require patience—often taking nearly a full year from planting to harvest—making them perfectly suited to the unhurried rhythms of Amish farming where speed rarely trumps quality.

7. Jerusalem Artichokes: The Native Tuber

Nothing about Jerusalem artichokes makes sense—they’re not from Jerusalem, nor are they artichokes. These knobby, irregular tubers grow beneath tall sunflower-like plants native to North America, making them one of few indigenous vegetables in Amish gardens.

Their crisp white flesh offers a sweet, nutty flavor somewhat like water chestnuts when raw or develops artichoke-like qualities when roasted. Many Amish families maintain patches that return year after year with minimal care.

Also called sunchokes, these tubers contain inulin rather than starch, making them historically important for people managing blood sugar—knowledge preserved in Amish communities where traditional remedies remain valued alongside modern medicine.

8. Scorzonera: Black Salsify’s Mysterious Appeal

With its snake-like appearance and coal-black skin, scorzonera might be mistaken for something inedible rather than a delicacy. Amish gardeners carefully dig these fragile roots, which can grow over two feet long when soil conditions allow.

Beneath the intimidating exterior lies creamy white flesh with a delicate, almost asparagus-like flavor. Traditional Amish cooks simmer the peeled roots in milk or cream, creating silky side dishes that complement hearty winter meals.

Growing scorzonera requires exceptional patience—the roots take two full seasons to reach maturity—exemplifying the multi-generational thinking that characterizes Amish agriculture where immediate returns often matter less than sustained traditions.

9. Hubbard Squash: The Winter Giant

Weighing up to 50 pounds with warty skin in shades of blue-gray, green, or orange, Hubbard squash looks more like decorative gourds than dinner. Amish farmers grow these massive squashes for their exceptional storage qualities and rich, sweet flesh.

A single Hubbard can feed a large family for several meals—important in Amish communities where families often include many children. The thick, hard shell protects the bright orange interior for months in cool storage.

Traditionally cracked open with an ax rather than a knife, these imposing vegetables transform into silky pies, hearty soups, and simple mashed dishes that sustain Amish families through long winters when fresh produce becomes scarce.

10. Mangelwurzel: The Forgotten Giant Beet

Resembling beets that have grown to monstrous proportions, mangelwurzels can reach the size of bowling pins—far too large for modern grocery displays. Amish farmers originally grew these massive roots primarily as livestock feed, valuing their high yield and excellent storage properties.

The name derives from German words meaning “mangel root,” reflecting the crop’s importance in preventing food shortages. While young roots and greens are perfectly edible for humans, most Amish families reserve the mature roots for animal feed during winter months.

These giants remain important in self-sufficient Amish farming systems where animals and humans share the bounty of the land according to each crop’s best use.

11. Luffa Gourd: From Vegetable to Sponge

Few vegetables transform more dramatically than the humble luffa, which starts as an edible squash and ends as a bathroom sponge. Amish gardeners harvest young luffas when they’re just 4-6 inches long, cooking them like zucchini in stir-fries and soups.

Left to mature on the vine, these same fruits develop an intricate fiber network inside. After soaking and cleaning away seeds and skin, the natural sponge emerges—perfect for washing dishes or bodies without synthetic materials.

This dual-purpose crop exemplifies the waste-not philosophy central to Amish farming, where a single plant might provide both food and practical household items through different harvest timings.

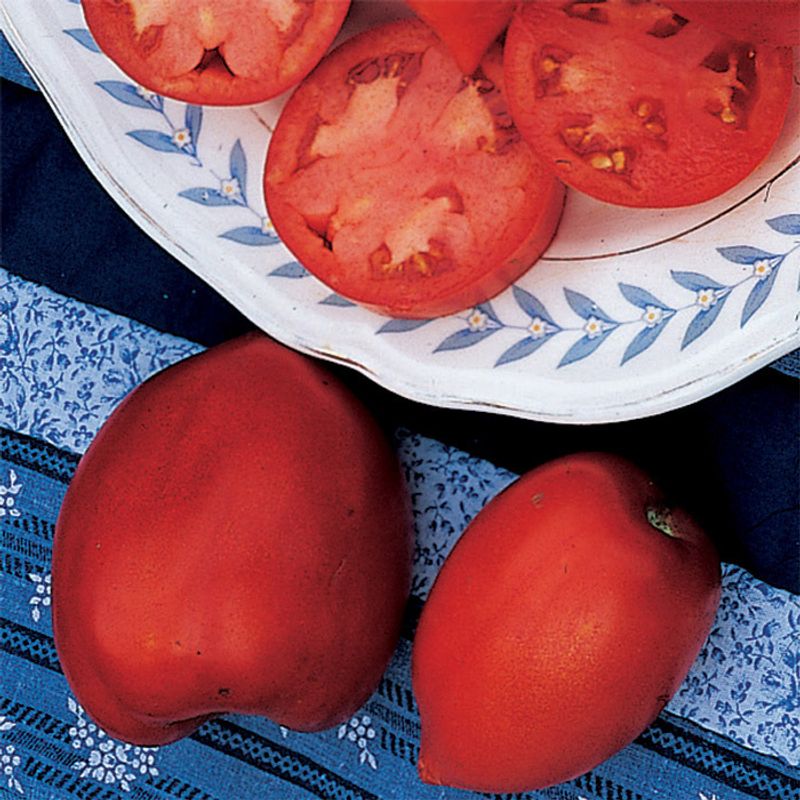

12. Amish Paste Tomatoes: Heirloom Canning Champions

Misshapen, often cracked, and lacking the uniform redness of supermarket tomatoes, Amish Paste varieties might seem inferior until you taste them. These egg or heart-shaped fruits contain remarkably little water and abundant sweet flesh—characteristics developed through generations of selective saving by Amish gardeners.

Summer canning days bring Amish families together as these dense tomatoes transform into sauces, salsas, and preserves that capture summer’s essence. A single plant might yield 20 pounds of fruit, making them efficient producers for large families.

Many Amish communities maintain their own slightly different strains, adapting the basic paste tomato to local growing conditions and flavor preferences over decades.

13. Yardlong Beans: The Incredible Stretchers

Dangling like green ropes from tall trellises, yardlong beans create dramatic vertical elements in traditional Amish gardens. Despite their name, these Asian beans rarely reach a full yard, typically growing 18-30 inches long before harvest.

Young Amish children often delight in finding the longest bean during harvest time, creating friendly competition while helping with garden chores. The flavor resembles green beans with added sweetness and a more substantial texture that holds up well in long-cooking dishes.

Particularly popular in Amish communities with Southeast Asian neighbors who introduced these heat-loving legumes, yardlong beans demonstrate how Amish farmers thoughtfully adopt useful crops from other traditions while maintaining their core agricultural practices.

14. Chicory Root: Coffee Without Caffeine

Blue-flowered chicory plants grace Amish farm edges with beauty before their gnarly roots are harvested for a practical purpose. When roasted and ground, these bitter roots develop a remarkably coffee-like flavor without caffeine—important in communities where stimulants are often avoided.

The preparation process requires patience: roots must be thoroughly cleaned, chopped, slowly roasted until dark brown, then ground for brewing. Many Amish families blend chicory with small amounts of real coffee, stretching expensive imported beans while moderating caffeine intake.

This practice dates back to American Civil War shortages and European traditions, representing the practical self-sufficiency that characterizes Amish approaches to daily needs.

15. Lovage: The Forgotten All-Purpose Herb

Towering up to six feet tall with hollow celery-like stems, lovage commands attention in Amish herb gardens despite being virtually unknown in modern kitchens. This powerhouse herb offers intense celery flavor from every part—leaves, stems, roots, and seeds—each harvested at different times.

Amish cooks add young leaves to soups and salads, candy the stems like angelica, and use the seeds to flavor baked goods. The roots, when dried, provide a year-round seasoning base for broths and stews.

A single lovage plant can produce for over a decade, representing the Amish preference for perennial crops that reduce yearly workload while providing consistent yields—practical thinking that modern agriculture often overlooks.

16. Walking Onions: The Self-Planting Alliums

Strange bulblets forming at the tops of green stalks give walking onions their curious name—they literally plant themselves as top-heavy stems bend to ground. Amish gardeners value these perennial onions for their minimal care requirements and three-part harvest: green scallion-like shoots in spring, summer topsets for pickling, and underground bulbs in fall.

Once established, walking onions maintain themselves for decades, slowly migrating across garden beds as new bulblets root. This self-sufficiency perfectly matches Amish agricultural philosophy where human intervention should complement natural processes rather than constantly fighting them.

Also called Egyptian or tree onions, these plants connect modern Amish gardens to centuries-old European farming traditions that crossed the Atlantic with their ancestors.

Leave a comment